Ethnography in Social Work

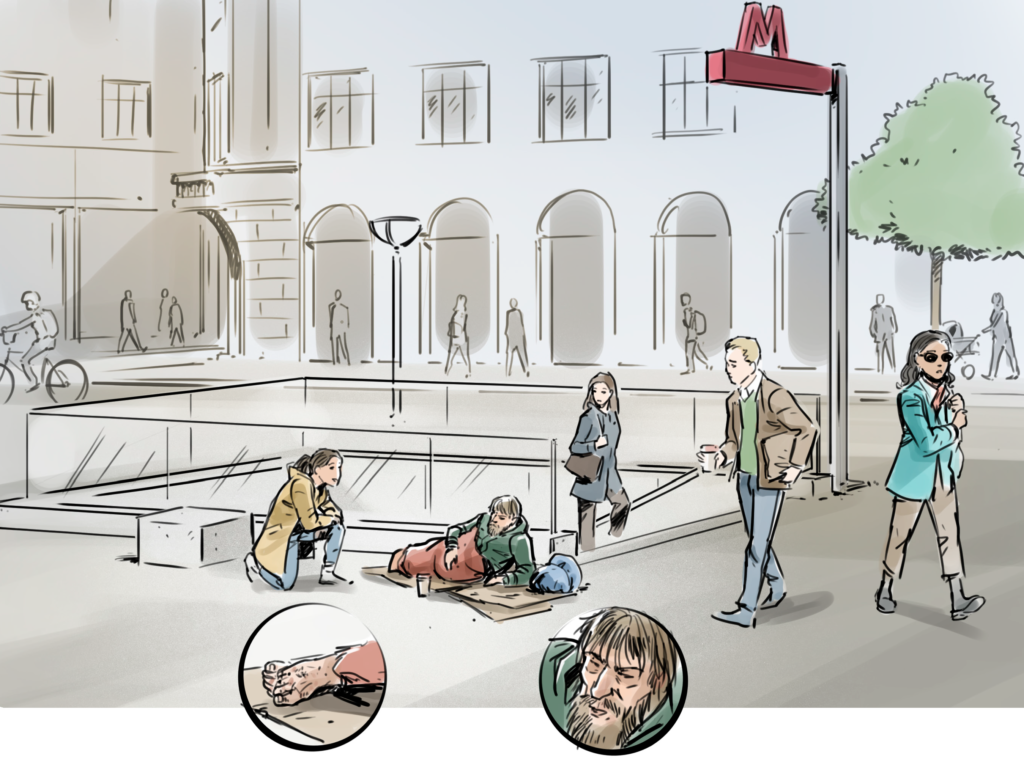

The theme rests on the belief that good social work practice often goes hand in hand with social workers’ ability to observe and consider very subtle details in the environment in which they work, and act and plan their work accordingly. In doing so, social workers can also become better at postponing the presumptions, conclusions, or judgments that we are usually quick to apply to things we see or hear.

According to Wendy Haight, Misa Kayama and Rose Korang-Okrah (2014), who have written about ethnography in social work, ethnography allows social workers to obtain in-depth knowledge about a context and environment, including the service users (and other actors) who inhabit the context. They underline that such in-depth understanding of a context is necessary in, for example, effective advocacy and for social justice purposes:

“Just as social workers seek a firmer grasp of their increasingly diverse clients’ everyday lives and perspectives, a goal of ethnographers is to understand what it means for people to be differently situated in terms of values, goals, resources, and social standing. Ethnographers seek to understand diverse individuals’ and groups’ complex systems of beliefs and practices as embedded within particular sociocultural and historical contexts.” (Ibid., p. 128).

It is important to understand that, while applied ethnography offers social workers some powerful tools, such as a more sensible ability to see, listen, and describe (as opposed to gaze, talk, and presume), it offers no road map to actions or better policy. Moreover, it is important to understand that, while ethnographic fieldwork is usually sustained over time and engaged with its research objects, most social workers will not have time to engage in ethnographic fieldwork. Thus, the strength of applied ethnography lies in its ability to offer social workers a position for describing, analyzing, and reflecting on our own practices—from a position outside the contexts that we often take for granted. Applied ethnography is about being present and postponing judgment; allowing one-self to notice details (and perhaps banalities) and arrive at unexpected insights; seeing your context in new ways.

At its best, this position can “…make visible the complex processes that cross the artificial divide between micro- and macrosocial work practice, showing the ways in which the actions of workers respond to and shape theories, organizations, policy and social conditions and vice versa.” (Gillingham & Smith 2020, p. 2235). Applied ethnography is an approach, and set of tools, which can enhance your understanding of the co-productive relationships between social and physical structures, human actions, and social change.