Keywords: Gentrification and financialization, urban development and marketization, urban commercialization, sense of belonging and place, spatial negotiation, organizational change

In this resource, you will find the case “Strive, Survive, Thrive?” and two related themes with each their questions, exercises and related materials:

- Theme 1: Urban planning and development—the challenges of gentrification and marketization

- Theme 2: Organizational change and socio-spatial consequences

You can jump to the different themes by clicking the title of the theme you wish to work with.

Read the case before continuing with the themes:

THEME 1: Urban planning and development—the challenges of gentrification and marketization

In the case, you are introduced to gentrification as a challenge to social work organizations and vulnerable urban populations. In this theme, you train your ability to distinguish processes of gentrification and financialization respectively. This skill will help you to qualify your analytical use of the two concepts.

A global tendency in urban planning and development has been a move from public sector-based development towards more involvement of private actors, especially private investors, adhering to market logic and profit making. As eloquently put by Helen Carter, Henrik Gutzon Larsen and Kristian Olesen (2015):

“Spatial planning practices and discourses are in a continuous flux. Over recent decades, governance reforms and political shifts in many countries have sought to reorient spatial planning once more. These changes have been analysed as neoliberalisations of spatial planning; that is, as processes in which planning is being recast to the wider neoliberal project of emphasising market relationships driven by logics of competition and effectiveness. Borrowing the vocabulary of Harvey (1989), it could be that spatial planning in many countries has shifted from stateled ‘managerialism’ to (supposedly) market-led ‘entrepreneurialism’”

(Helen Carter, Henrik Gutzon Larsen and Kristian Olesen, 2015 p. 2)

This means that processes of urban renewal leading to, for example, an increase in housing prices, can no longer be understood solely through the concept of gentrification. Instead, urban planning and development that involves marketization, privatization, and commercialization, must be understood as expressions of financialization (Sassen 2018).

Financialization is characterized by the fact that processes of urban development have been integrated into a global economy. Consequently, the scales upon which investment and development rest can be large, and untransparent to most people, and an urban area can change quite quickly with the influence of large foreign investments. In other words, our cities have become objects of investment.

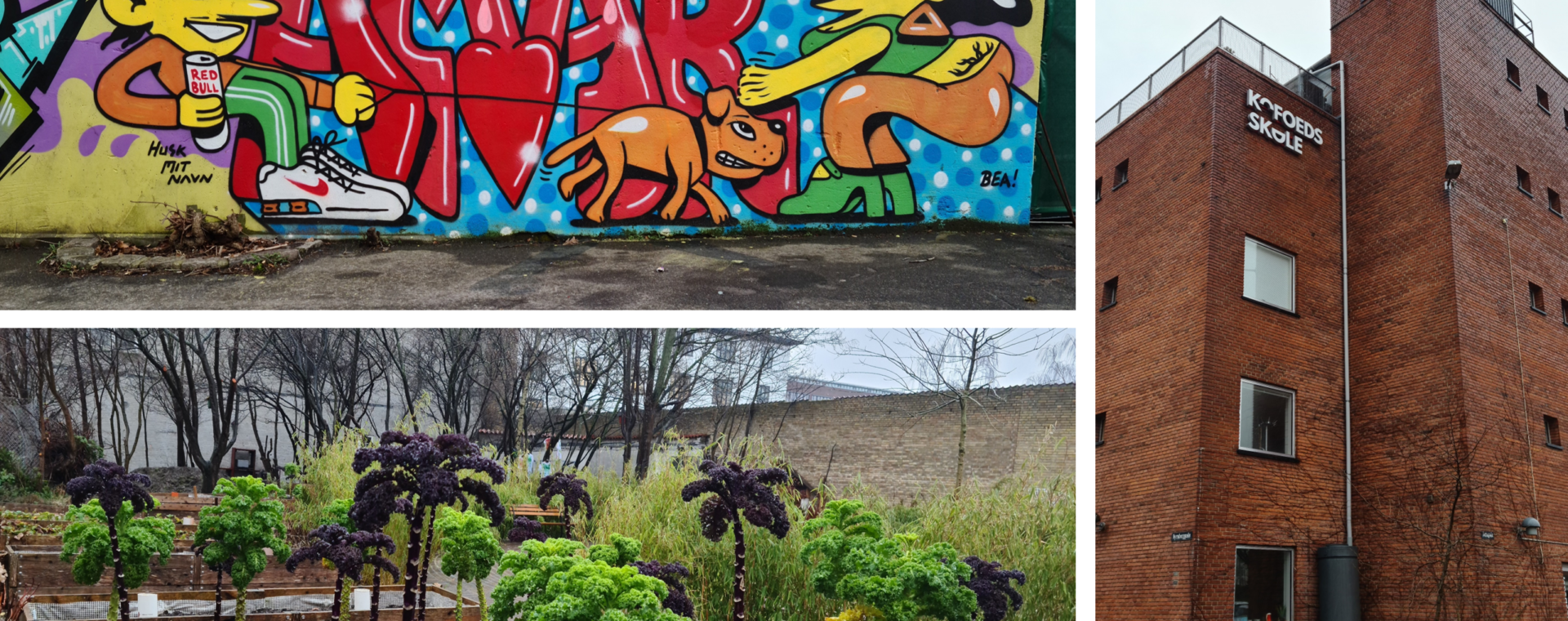

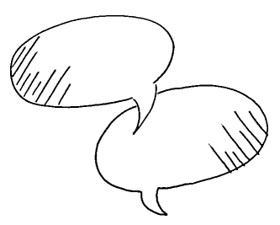

In Copenhagen, the area where Kofoeds School is located is one example of the socio-spatial consequences of this trend. Another recent example is the Postal Lot [Postgrunden]. This area is in the city center, tugged in between one of the newer beach parks made for recreational purposes, Tivoli, the central station, and close to one of the newest up-and-coming urban spaces catering to the hipster crowd of Copenhagen, the Railway Depot [BaneGaarden], a former industrialized area located between Vesterbro and Sydhavnen. The state has sold the Postal Lot to one of Denmark’s largest pension funds and an American investment fund. Despite a lack of affordable housing and common spaces in Copenhagen, the buildings and lot are being converted into four major towers providing a luxury hotel, 160 luxury rental apartments and a shopping center. From a critical point of view, the challenge is that by privatizing what used to be publicly owned, the state and municipality have surrendered their power to set demands for a certain diversity in the kind of housing that is being built in the city (e.g., in terms of size, form of tenure or ownership construction, residency requirements etc.). Consequently, a uniform process of urban renewal and development is promoted, namely a process catering mostly, or solely, to wealthy urban dwellers. So, is this kind of urban development unique to Copenhagen? No, would be the short answer, because processes of financialization resulting from neoliberal developments such as a heavy emphasis on privatization and marketization of the housing sector, can be observed all over the world. But, of course, the specific local experiences, challenges, and dilemmas related to the local development are unique to the Copenhagen context.

To exemplify the scale and size of this issue, we refer to city planner and urban policy consultant Bruno Marot (2021). Marot is working with the socio-spatial consequences of financialization especially in the global South. According to him, from 1991 to 2015 financial investments in real estate grew from around 1 billion to 430 billion US dollars (Ibid.):

“It is often said that the form and socio-spatial organization of cities reflect the way in which they are financed. In this sense, the 141% increase in the number of skyscrapers since 2010 is revealing of a constantly growing phenomenon: that of the financialization of city-making.”

(Marot, 2021)

Based on the case, start by listing the processes of gentrification and financialization tendencies respectively. Based on your list, discuss the following:

What are your arguments for listing the processes as gentrification and financialization respectively?

Which role does the actors’ position (for example, global economy, private, public, or civic sector, the extent to which they depend on collaboration with local actors and policies etc.) play in your argumentation?

Research the ways in which urban planning and development is organized in your city. Discuss the socio-spatial consequences of this organization.

THEME 2: Organizational change and socio-spatial consequences

In the case, you are introduced to some of the changes Kofoeds School has gone through over the last decades. Some of these changes are related to more general changes in social policymaking and funding at municipal and state level. Others, though, are related to socio-spatial issues such as a sense of place and belonging for individual students and teachers, or groups of students and teachers, at the school. In this theme, you will focus on the socio-spatial dimensions of organizational change. The purpose is to train your ability to analyze the ways in which people and groups are affected by, and resist or adapt to, organizational changes at a socio-spatial level. You will also become more aware of the ways in which conceptual and theoretical knowledge about place might qualify social workers role in processes of organizational change.

In the case, you are briefly introduced to a critical theoretical understanding of place (p. 13). It is an understanding of places as material, imagined, lived, affected by rhythms, connected across scales from the global to the individual level, contested and saturated with power (cf. Lefebvre 1991, Cresswell 2014). According to geographers John Agnew and Tim Creswell, place can be understood as consisting of three elements: Location (the objective position, a “where”), locale (the physical and social context of a place, a “what”), and sense of place (the individual or collective meanings attached to a place). Thus, in their perspective, physical, economic, and organizational changes are interrelated, and people’s sense of place and belonging will always be affected by changes in either one of the dimensions.

Based on the people you meet in the case, discuss the following:

- In relation to the changes, physically as well as organizational, what are then the strengths and challenges of their sense of place and belonging?

- What role does their power position (for example, as ‘newcomers’ or ‘old-timers,’ professional or student, ‘change-agent’ or ‘traditionalist’, etc.) play for their sense of place and belonging?

- In which ways could the processes of changes have played out differently if the professionals have had a more theoretical understanding of place from the beginning?

- Knowing what you now know about place, gentrification and planning, how would you plan a more participatory approach to organizational change with socio-spatial consequences?

Extra material to “Organizational change and socio-spatial consequences”

You can learn more about place and the sense of place as one of three dimensions of place in the theme What is ‘a place’? Towards a theoretical understanding of place and place-making.

Listen to the podcast The 3 lives of the Lioness. The podcast is in three episodes. In episode one and two you can become more familiar with the ways in which a person in an exposed position experiences and uses the city. In the third episode you can listen to the Lioness telling her story of how having a sense of belonging to a place like Kofoeds School has helped her to recover from years of drug use and life on the streets.

COMING SOON

References

Carter, H., Larsen, H.G. & Olesen, K. A. “Planning Palimpsest: Neoliberal Planning in a Welfare State Tradition”, Refereed Article No. 58, June 2015, European Journal of Spatial Development, URL: http://www.nordregio.se/Global/EJSD/Refereed articles/refereed58.pdf

Cresswell, T. (2014). “Place.” In: Lee, R, et.al. (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Human Geography. London: Sage

Lefebvre, H. (1992). The Production of Space. Wiley-Blackwell

Marot, B. (2021). “Financialization of Cities: A new challenge for cooperation and development stakeholders” https://ideas4development.org/en/financialization-cities/

Sassen, S. (2018). Cities in a World Economy. 5th Edition. Sage.